As I step out of the air-conditioned mall and into the blistering heat, a man shoves a bag of socks in front of my face and gives me his sales pitch in Arabic. Outside the mall, there are vendors in the street selling clothes, electronics, water bottles, nutritional supplements, and just about anything else you can imagine. Everywhere I go throughout the entire city, people are shouting, haggling, and otherwise trying to sell goods of all types at outrageously low prices. And all of this shouting and haggling, combined with the diversity of goods being sold give this city a feverish and chaotic energy that is unlike anywhere I have ever been.

I am in Ciudad del Este, the second largest city in Paraguay.

A suit jacket being sold in a mall in Ciudad del Este for 7 USD.

During the past six months, I have visited 8 Spanish speaking countries in South America: Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay. And after visiting all these places, I think that they can be divided into two groups: Paraguay, and not Paraguay.

Despite being in the geographic center of South America, this country is truly unique. It has its own history and culture that make present-day Paraguay very different from its neighbors.

Additionally, it is relatively unknown to the rest of the world. It is one of South America’s least visited countries, and is rarely reported on by international media. Prior to arriving in Paraguay, Gabe and I referred to it as the “black hole,” since despite extensively researching all of the countries we planned to visit, we failed to find much information about present-day Paraguay. Even most of the other travelers and locals we met in South America knew nothing about this country.

And this is truly a shame, since Paraguay is an incredible place to visit! It has beautiful landscapes, its own unique national culture, a variety of interesting immigrant communities, and is home to some of the nicest people I have ever met. It also has an electrical grid powered entirely by clean energy, produces (arguably) the best pineapples in the world, and is one of the only places in the Americas where an indigenous language is taught in schools.

In this post, I will talk a little bit about Paraguay, my experience spending over a month there, and what makes the country so unique.

Overview

I entered Paraguay planning to spend a week, and ended up spending a month. During that time, I Couchsurfed, hung out with Paraguayans, and visited a few cities and small towns in different parts of the country. I wanted to stay even longer, but decided to leave early after contracting chikungunya, a debilitating mosquito-borne illness.

Paraguay was also the place where Gabe and I parted ways after four and a half months of traveling together. He had a flight from the capital city of Asunción back to the United States, where his new job was about to start. I opted to stay two months longer in South America, which I spent in Paraguay, Argentina, and Chile.

In my opinion, Paraguay differs from other South American countries in two, seemingly contradictory regards: its strong indigenous influence and its strong international influence. Both are deeply rooted within the country’s unique and fascinating history, which I encourage you all to read about in its Wikipedia article.

But for those of you who are in a hurry, I will give you the short version. In Paraguay, indigenous people were subject to far less repression than those who lived in other parts of the Spanish empire. This resulted in Spanish colonizers learning indigenous languages, rather than the other way around. The language and culture of one particularly large group, the Guaraní, went on to become part of the national identity for all Paraguayans, regardless of ancestry.

A welcome sign on the Paraguayan border in Guaraní, Spanish, Portuguese, and English. Notice how Guaraní is emphasized over the other languages.

The international influence comes from lax immigration policies which have existed for much of Paraguay’s history. These policies arose in the 1880’s after the War of the Triple Alliance, a war which pitted Paraguay against an alliance made up of Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina. Paraguay, although in those days considered South America’s most advanced country (1), simply stood no chance. Brazil alone had more soldiers than Paraguay did people. As a result, the country was devastated. Paraguay lost over half its population and over 90% of its men, and the war only ended when the Paraguayan president himself was killed in combat.

The slaughter forced the country to implement a number of extreme policies to prevent a population collapse. Two well-known policies were temporarily encouraging Catholic priests (who are normally celibate) to practice polygamy, and promoting heavy immigration from around the world. The immigration policy proved to be much more durable, and now Paraguay has sizable populations of people from around the world, with the largest being from Germany, Japan, and Lebanon.

As a result of these two major parts of the country’s history, Paraguay is seemingly a land of contradictions: a land where nearly everyone is fluent in Guaraní, yet where indigenous people only make up only several percent of the population (2). And a land where you can get traditional Paraguayan classics, like bife de chorizo, served with shawarma and German beer.

Ciudad del Este

My first stop was the country’s second-largest city, Ciudad del Este (literally: City of the East). I entered the city by crossing the border with Brazil at the Brazilian city of Foz do Iguaçu. Ironically, I was only in Foz do Iguaçu to see Iguazu Falls, and had not planned to cross into Paraguay. But all throughout the city of Foz do Iguaçu, there were billboards advertising a place called Mona Lisa just on the other side of the border in Paraguay. The billboards offered no information except for the name Mona Lisa, so I was intrigued, and Gabe and I decided to go. As with the rest of the country, I truly had no idea what to expect, and went without expectations.

Iguazu Falls in Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil.

Upon getting off the bus in Ciudad del Este, I was glad no one tried to describe Ciudad del Este to me, since the city is nearly indescribable. Throughout the streets, sidewalks, parks, and walkways near the bus stop were people selling an assortment of manufactured goods: clothes, shoes, hats, electronics, kitchenware, and anything else you could imagine. It was like someone had dumped an Amazon fulfillment center in the street, then sent its employees to aggressively court you to buy the goods.

Upon closer inspection, I realized something unique about the buildings as well. There were no office buildings or restaurants or other types of buildings typical of most cities. As far as I could see, every single building was a mall or department store. It was as if the only reason Ciudad del Este existed was to sell me stuff. And in a way, I was right.

Despite being founded only in 1957, Ciudad del Este has grown to Paraguay’s second-largest city. It has a population of around 400,000. The city was originally founded as a base for workers constructing the Itaipu dam, one of the world’s largest hydropower dams. But due to its strategic location on the triple-border with Brazil and Argentina, combined with government corruption, it quickly became a hub for people smuggling drugs and stolen goods.

The trade of illicit goods only grew over the following decades. In addition to the bounty of drugs and stolen goods that were sold in Ciudad del Este, the Paraguayan government signed an agreement to allow China to import goods to the city tariff-free, which led to a proliferation of cheap, factory-made goods. Many of these imported products were copyright infringements, shipped to Ciudad del Este tariff-free, then sold across South America. The government corruption and profitability of illegal goods were so great that enforcement of the laws was virtually non-existent, even when pirated movies were shown in theaters! (3)

The situation peaked in the early 2000’s, when illicit goods made up 22% of Paraguay’s GDP and the United States was considering sanctioning the country because unlicensed songs sold in Paraguay alone costed U.S. companies $125 million per year! In those days, a businessman from Ciudad del Este interviewed by the New York Times put it best:

”Anything you want, you can buy here…legal, illegal, whatever. (3)‘

The Ciudad del Este I visited in 2023 very much reflected this history. It is now largely a place for comparatively wealthy Brazilians to do some cheap shopping. With cheap, often illicit, products arriving by boat from China, Ciudad del Este offers an endless array of goods at outrageously low prices. And the quantity of goods bought and sold in the city is so large that it is now one of the world’s largest free-trade zones—comparable in magnitude to Hong Kong or the Panama Canal (3). These goods ranged in quality from obviously counterfeit electronics sold by street vendors for just a few dollars all the way up to boutique malls selling expensive artwork.

And the nicest mall of all? Mona Lisa.

Entrance to Mona Lisa (image from TripAdvisor).

It was in and around Mona Lisa where Gabe and I spent most of our time. It was heavily air-conditioned, which we really appreciated during Ciudad del Este’s 100-degree afternoon. In and around the mall, people spoke almost exclusively in Portuguese. Brazilians—easily identifiable because they always wore flip-flops—filled the mall every day, and all the Paraguayan salespeople spoke Portuguese to accommodate them.

Many of the people did not know what to make of Gabe and I. We were obviously not Brazilian, nor Argentinian, nor Paraguayan, and we were told that gringos like us hardly ever visited Ciudad del Este. A few people even tried to speak to me in German, thinking that I could be one of the many Mennonites who live on the other side of the country, but my confused looks always told them otherwise.

But what surprised me most of all about my time in Paraguay was the difference between the culture of the city and of the Paraguayans who lived in it. Ciudad del Este was like the Wild West: lawless and chaotic. One person even told me to stay out of trouble while in the city, since if anything happened to me not even the U.S. government would be able to help.

Once getting past the marketing and the sales pitches, however, I found that the Paraguayans I met were nothing like the city. They were all kind, interesting people. I met a saleswoman around my age who was working to put herself through college. She told me that her mom was Paraguayan and her dad German, and that she was fluent in Spanish, Guaraní, German, and Portuguese, and that she was studying English because she wanted to work in tourism. I also had a taxi driver who told me he moved to Ciudad del Este from a poor farming town several decades prior and became the only person in his family to escape poverty.

As I would later learn, Ciudad del Este is a good metaphor for Paraguay as a whole. It can be corrupt and lawless, but is full of good people who are just doing what they can to survive.

Filadelfia

After spending a few days in Ciudad del Este, Gabe and I headed to the small town of Villarrica. After a few days there, we went to the capital city of Asunción, where Gabe flew back to the United States. I then left Asunción for my first solo adventure, a three-night stay with a Mennonite family in the town of Filadelfia, Paraguay. There, I would learn a bit about their history and culture

Despite being in the same country, Filadelfia felt a world away from the rest of Paraguay. And in some ways, it felt like I was in a small town in the United States.

The center of the town was full of large, heavily air-conditioned grocery stores mixed among car dealerships and farm equipment stores. People drove around the center of the town in big pickup trucks, often loaded with agricultural tools.

Outside the center were houses, often quite large. Each one was widely spaced apart and had a front and backyard and a gate separating the yards from the street. Wide roads criss-crossed the neighborhoods, reminding me of the suburbs of Texas.

It was in one of these neighborhoods where my hosts lived, Rudolf and Juliane.

As their names suggest, they were both native German speakers. They, like most of the people in the town of Filadelfia, were German-speaking Mennonites, who are confusingly called Russian Mennonites. And the story of how they ended up in Paraguay is an interesting one.

Mennonites are Christians, and their sect was formed in a German-speaking part of what would eventually become the Netherlands in the 1500’s as part of the Reformation. They arose from the Anabaptists, a group that also gave rise to Hutterites and the Amish. Like these groups, Mennonites tend to live in small communities made up of fellow believers. Unlike the Amish, however, they do not reject the use of modern technology.

Like many religious reformers of the era, they were deemed blasphemous and heavily persecuted. Some groups of Anabaptists violently opposed their persecution, leading to an escalating cycle of violence.This violence horrified the Mennonites, leading them to become pacifists who hold harmony in the community as one of their highest values.

To escape persecution, a group of Mennonites migrated from the Netherlands to Russia in the 1700’s, where they were offered religious tolerance and exemption from military service. These migrants would eventually become known as Russian Mennonites, despite maintaining their Dutch-German traditions. This arrangement continued until the end of the Bolshevik revolution in 1923, at which point the Communist government revoked their special religious status and forced many into military service.

This triggered a mass exodus of Russian Mennonites. A few groups made a deal with the Paraguayan government in which they would develop agriculture in the remote West of the country in exchange for exemption from military service and land to build farms and communities. In 1930, one group of Mennonites established a community in Paraguay and called it Filadelfia, Greek for “the city of brotherly love.” Among these people were Rudolf’s parents, who at the time were just young children.

Rudolf told me this story one morning as we shared tereré, a popular Paraguayan drink. Like Guaraní, tereré is an indigenous invention that has become part of Paraguayan culture. It is so ubiquitous in the country that it would be no understatement for me to say that every single Paraguayan drinks tereré every single day. I even saw reporters drink tereré while delivering the morning news! And like Guaraní, tereré is virtually unknown outside the country.

Tereré was the inspiration for the much more widely-available yerba mate, made from hot water and yerba: dried leaves and stems from Ilex paraguariensis, the yerba mate plant. Tereré, however, is made from iced water steeped with a mix of fresh herbs called pohá ñaná (I cannot pronounce it either, it’s Guaraní). The water is then poured over yerba and drunk through a filtered straw, just like yerba mate.

Cold water steeped with pohá ñaná alongside a cup full of yerba and a filtered straw; the ingredients for tereré.

The typical way of consuming tereré: with a thermos full of cold water and pohá ñaná dispensed into a metal cup full of yerba and a filtered straw. Nearly every Paraguayan has one of these, and the leather thermos cover is often customized with designs and the name of the owner.

There is nothing in the world that quenches the stifling Paraguayan heat better than a good cup of tereré, and the secret to a good cup of tereré is good pohá ñaná. In Paraguay, you can see people mashing this aromatic mix of herbs in the street to sell every morning. I never was able to find out what herbs made up the mix, nor could I find them for sale outside of the country. If I want to enjoy this drink, you will have to head to Paraguay and get it from the source.

Anyways, back to Filadelfia.

Rudolf told me that, to him, the most important part of being a Mennonite means living harmoniously. This goes beyond pacifism to include community ownership of many enterprises and a system of mutual support among Mennonites.

Many of Filadelfia’s largest businesses, like the grocery store and the agricultural hardware store were run in a co-op fashion, meaning that the leaders were elected by the community, rather than a board of directors.

Additionally, I learned that Juliane was Rudolf’s second wife. His first wife died of cancer about ten years prior. And he told me that through every step of the grieving process, someone from the community was with him to provide emotional support and help him keep up with his work and finances. He told me the support he received was essential in helping him overcome his loss, and is the reason why he has never in his life considered leaving Filadelfia.

The tradition of mutual support stretches all the way back to the very beginning of Filadelfia’s history. In the beginning, the settlers struggled to produce any food, since the climate of western Paraguay is unlike that of Russia. They sent out a request for aid to the Mennonite Church, and a Mennonite agronomist from the United States dropped everything to come to Filadelfia and help. He taught the people how to farm in the hot, arid climate, and was responsible for the colony’s success (4).

In the present day, Filadelfia is now one of the wealthiest parts of Paraguay. This wealth has brought many non-Mennonites from other regions of the country looking for work. It has also made Filadelfia an epicenter of deforestation in the country.

These changes have brought tension to the community. There now exists friction between ranchers and environmentalists as well as new residents and old ones. The town has endured many hardships since its founding, and perhaps if it extends its ideals of harmony and brotherly love beyond the Mennonite community and to all of FIladelfia’s residents, it will be able to overcome these challenges as well.

Posing with a Samu’u tree near Filadelfia, Paraguay. Samu’u trees have wide trunks that store water and help the trees survive droughts, just like the baobab trees of Africa. Every few years, there is a national contest complete with a cash prize and bragging rites to find the widest tree. This one was the winner in 2018.

Taguá, a critically endangered Paraguayan boar. They are currently being re-introduced through a captive breeding program that is run by a museum employee who lives just outside of Filadelfia.

Luque

After Filadelfia, I headed back to Asunción. But rather than stay in the city itself, I opted to stay in Luque, a city that is adjacent to Asunción. From there, I visited la Universidad Nacional de Asunción in nearby San Lorenzo, the most important university in the country. Since the university is closed to outsiders, I was given a tour by Sofia, a biology student whom I met the first time I was in Asunción.

In the university, we went to the biology labs, since I also used to study biology. There, it was a small, close-knit community where everyone knew everyone else. This allowed Sofia to introduce me to some of the people working in the labs, where they told me a bit about their research.

Not just in Filadelfia, but throughout Paraguay, large swathes of land are being cleared to make room for soy and cattle farms. This has been a disaster for many of Paraguay’s native species, and the biologists were looking for ways to conserve Paraguay’s many unique animals.

But when they were talking about the specific animals they researched, I quickly realized I had no idea what they were talking about. This is because the influence of the Guaraní language is so strong that even when Paraguayans speak Spanish, they still use the Guaraní word for many things, including animals. Anteaters were called Jurumi or Kaguare, depending on the species. These names were very different from the Spanish one, oso hormiguero, which translates to anthill bear.

I then asked if they do most of their research in Spanish or Guaraní, and they told me Spanish. They explained that, in urban Paraguay, where most people speak both languages, the languages are used in very different contexts. Spanish is for work, school, and formal interactions. This means that in many places, it can be considered rude to address a stranger in Guaraní, even when you both speak the language.

Alternatively, Guaraní is reserved for family, friends, and telling jokes. They told me that Guaraní is a fun and playful language, and that jokes told in Guaraní are way better than jokes told in Spanish.

But since I had no knowledge of the language, I could not understand what they meant. I failed to pronounce even the most basic words in Guaraní. To me, the language sounded utterly unlike anything I had heard before, and most outsiders would agree. A former U.S. ambassador to Paraguay succeeded in learning Guaraní, and described the process as “probably harder than Chinese.” And even after years of study, one Paraguayan politician described his Guaraní as ”stammering.” (5)

But regardless of my inability to understand Guaraní, talking to them reinforced something I had suspected since I arrived in Paraguay: that Paraguayans are among the nicest, friendliest people I have ever met.

Throughout my time in Paraguay, I would meet a stranger on the street, then ten minutes later find myself listening as they tell me their life’s story. I also found it really easy to find someone who was willing to let me stay at their place. And no matter how hard I tried, my hosts would never let me pitch in to help cook or pay for meals. They considered it their obligation as hosts to take care of me.

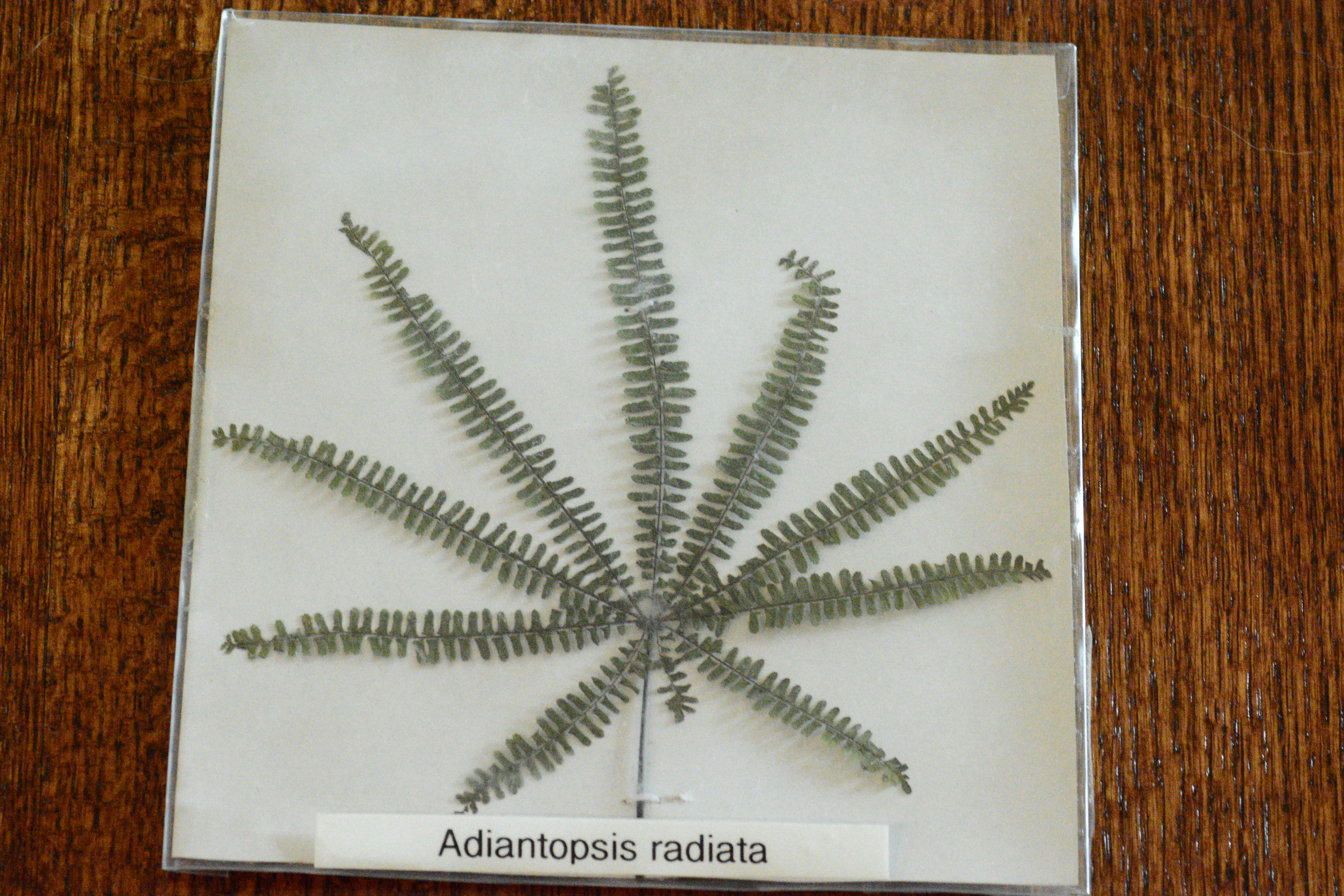

Sofia and her fellow biologists continued this tradition of hospitality. By the time I left the university, they sent me away with a Guaraní and Spanish-language guide to Paraguayan mammals, a guide to fish of the Paraná river, and a pressed leaf from one of their favorite native plants. All of this they gave me without my asking, and would not take no for an answer.

A pressed leaf from Adiantopsis radiata, or culandrillo, a fern that grows along streams and wetlands in Paraguay.

I wanted to stay longer in Paraguay, and Sofia put me into contact with someone she knew who worked for a environmental nonprofit in Paraguay. After learning I was a biologist and outdoor guide, they offered to host me in one of their preserves for two weeks so that I could work on surveys and talk to their park rangers.

I readily agreed, only to have my plans derailed at the last minute. For the time I had been in Asunción, I had been ignoring the massive outbreak of chikungunya, a mosquito-borne disease, that had been affecting the city. A number of people who I had met in Asunción either had or knew someone who had the disease. And before long, I became one of those people.

A few days before I was supposed to leave for the preserve, I woke up in the middle of the night sweating and with a high fever. A trip to a medical clinic the following day confirmed that I had caught chikungunya, a mosquito-borne illness that had reached epidemic levels in the Asunción area.

In a medical clinic being treated for Chikungunya.

Debilitated by the disease’s characteristic high fever and severe joint pain, I had no choice but to cancel my plans. Instead, I booked a motel room and filled it with snacks and painkillers, where I would stay in for the next five days. The experience was so painful and trying that the only thought on my mind was to get as far away from the chikungunya outbreak as possible. So as soon as I felt better, I crossed the border into Argentina, where I immediately began to miss being in Paraguay.

- R. Phillimore, A Statement of the Facts of the Controversy Between the Governments of Great Britain and Paraguay (William Moore Printing, 1860).

- “Situación de las mujeres rurales” (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2008), (available at https://web.archive.org/web/20120118042911if_/http://www.rlc.fao.org/es/desarrollo/mujer/docs/paraguay/par03.pdf).

- D. J. Schemo, In Paraguay Border Town, Almost Anything Goes. The New York Times (1998), (available at https://www.nytimes.com/1998/03/15/world/in-paraguay-border-town-almost-anything-goes.html).

- Museo Casa de la Colonia.

- US ambassador on song in Paraguay. BBC (2008), (available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/7485088.stm).