Much of the time we spent in Bolivia was on a journey that had us almost constantly on the move and took us from high up in the Andes down into the Amazon Rainforest. We started in the city of La Paz then spent three days walking down an old Incan Road called El Choro, then taking various colectivos down the eastern side of the Andes to get to the town of Rurrenabaque, then leaving from Rurrenabaque for two different trips: a boat tour of a wetland called Las Pampas, and a trek through the jungle in Parque Nacional Madidi.

The several legs of this trip all started as independent ideas. We had long planned on hiking El Choro, one of the most popular treks in Bolivia. We also both wanted to see wildlife, which is everywhere in Las Pampas. And finally, we had been looking for treks in the Amazon Rainforest itself.

It turned out, Rurrenabaque offered both wildlife and Amazon Treks. Then when I looked at a map, I realized that the end of El Choro was between La Paz and Rurrenabaque. With some planning we could avoid backtracking and minimize the amount of time we spent traveling by leaving La Paz, hiking El Choro, then going straight to Rurrenabaque for our two tours.

During the planning of the trip, I really did not expect much of a challenge. The mileage of El Choro was well within the range of what I was used to, and I could not imagine the Amazon being any hotter than Texas during the summer. But as I would find out over the course of the trip, I overlooked a lot of potential difficulties, which resulted in this excursion being one of the toughest of my life. That being said, it was also an incredible experience, and one I would do again without hesitation.

El Choro

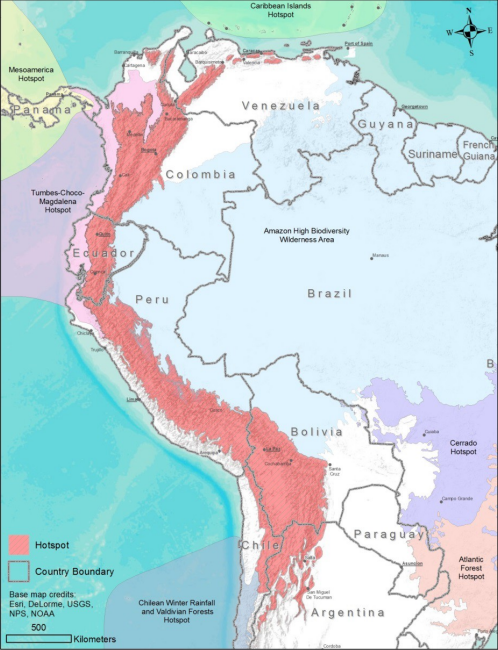

El Choro is a stone road built by the Inca in the 15th century. It starts high in the Andes at over 15,000 feet in elevation, and descends about 10,000 feet over 34 miles to the town of Korisamaña. Its original purpose was to facilitate the transport of goods between the heart of the Incan empire high in the Andes and the hot, humid jungle below. It is just one piece of a much larger network of Incan Roads that spans from Colombia to Chile. El Choro, however, one of the more popular of these roads, as it is well-preserved and traverses spectacular terrain.

To get to the El Choro trailhead, we left La Paz around for a town called La Cumbre. In La Cumbre, we found a few buildings and a sign with a map of El Choro. We followed the sign, which took us to a dirt road. According to the map, the dirt road climbed about 2 miles to the top of a pass, before descending for the rest of the trek.

Gabe and I spent the next 30ish minutes debating whether or not to attempt the pass that day. It was cold outside, looked like it was about to storm, and well past 3 in the afternoon. If we committed to the pass, we would have just a few hours to hike up one side and descend the other, since in that part of Bolivia it got dark around 6:30.

Additionally, we risked facing heavy rain and potentially snow at the higher altitudes. Whereas if we stayed in La Cumbre, we could look for a sheltered place to spend the night and hike the pass the following morning. We ended up choosing the latter, only to change course and hike the pass that afternoon, when we found that every single building in town was locked and unoccupied. So with a certain vigor in our pace that comes from a fear of being stranded in an alpine storm with just an a-frame tarp for a shelter, we made it to the pass in less than an hour!

Me, atop the pass.

From there, we managed to descend 8 more miles after the pass, which took us through a number of small villages. Like the town of La Cumbre, many of these villages were completely uninhabited. In one of the larger towns, however, there was a crowd of people gathered to watch a youth soccer game. There, we stopped for a few minutes to talk to a group of curious spectators. I asked one of them why there were so many abandoned towns, and he told me that many were used seasonally by sheep and alpaca herders, and that many were simply not in use at the moment.

El Choro running through one of these seasonally-occupied villages.

As darkness began to fall on the mountains, we felt like we had descended enough to avoid the worst of any potential storm. We found a nice clearing, set up the a-frame tarp, ate some peanut butter and bread, then went right to sleep.

We were right about both the storm and the location. It rained hard all night, but we stayed warm and dry.

View the following morning from beneath the tarp.

By morning, however, the rain had stopped. We were up early and immediately started hiking. As we walked further downhill from camp, the terrain changed dramatically. Within the first mile or two of walking, the environment changed from the relatively barren altiplano to a dense, green jungle. We were in the cloud forest and, fittingly, it began to rain. I started to feel like I was back in Parque Nacional Sumaco.

But the rain was not very heavy and the temperature was quite nice, so it was quite comfortable. As we walked, we passed a number of small towns, and each had a shop that looked like it was made to sell snacks to hikers. But most of the towns were empty, and in the ones that did have people the shop was always closed.

In one of these towns, we came across a lone man who was cutting firewood. Like everyone I had ever met in rural South America, he was very friendly, and we talked to him for a while. He told us all the shops were closed because no one had hiked the trail in nearly two weeks!

The reason?

The world cup started two weeks ago!

An empty town on the trail.

In the afternoon, the light drizzle turned into pouring rain right as we passed through a clearing with a shade canopy and a few locked wooden buildings. We sheltered from the rain there, and hoped to wait it out.

But the rain continued relentlessly, and as I waited, I felt my legs stiffen and seize up in a way I had never experienced before.

Places that had hardly been sore before in my life, like my toes, hip flexors, and shins felt borderline unusable. And Gabe was having similar soreness.

We talked about why a relatively easy day of hiking had made us so weirdly sore, then realized the culprit. It was all the downhill hiking!

Coming into El Choro, I was an experienced hiker. I had submitted peaks, hiked 30 mile days, and backpacked for weeks at a time. But never in my life had I walked 15 miles exclusively downhill like I did that day. It pushed my body in ways it had never been pushed before, causing me to be very sore in places I had never been sore before.

So even when the rain eventually did let up, we decided to stay put for the rest of the day.

But as is often the case with soreness, it was even worse the following morning. Just to get moving, I had to massage my legs and take a few ibuprofen and chew some coca leaves. They helped, but it was a struggle to hobble those final nine miles to the end of the trail.

During those nine miles, I was rewarded for my struggle with occasional sweeping views of the jungle and mountains around us. The forest here was unlike anything I had seen before, even different from Sumaco in ways that I cannot figure out how to articulate. And thanks to the incredible landscape, I managed to enjoy every painful step of that hike until we arrived in Korisamaña, our final destination.

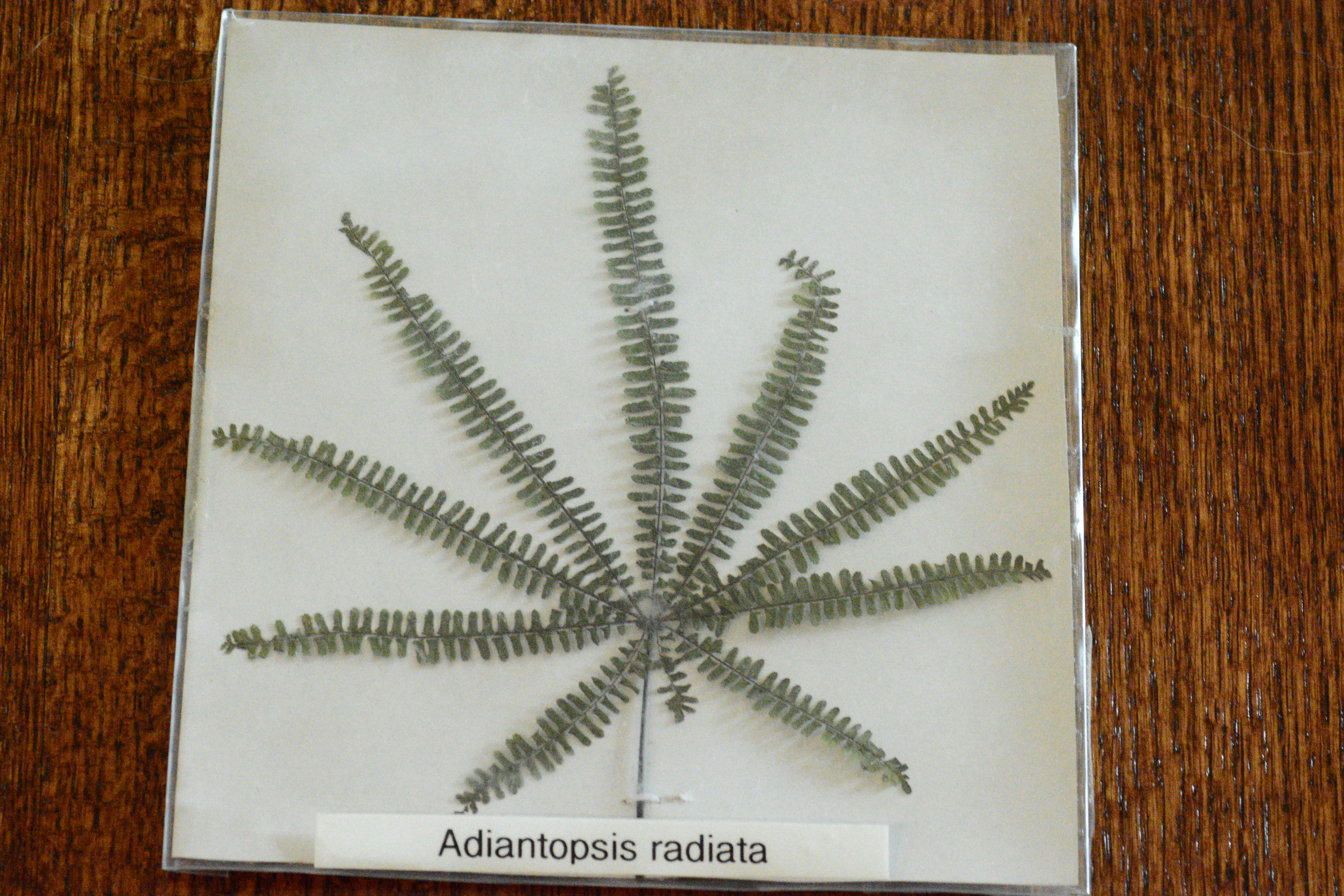

View of the jungle near Korisamaña. Fun fact: that tree in the middle is not a palm, but a tree fern, which are common throughout the Andean cloud forests!

In Korisamaña, the store was actually open, and the guy working inside made us sandwiches for lunch. As we talked to him, he confirmed that he, too, had not seen anyone hike the trail since the beginning of the World Cup. And despite the fact that it was December, he said we were the first travelers from the United States he had all year.

To Rurrenabaque

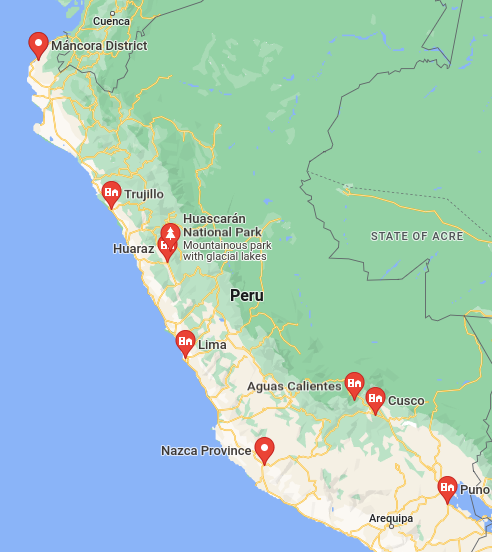

From Korisamaña, we took a taxi to the nearby city of Coroico. From Coroico, Rurrenabaque was just two colectivos away. The first was to Caranavi, about two hours away. The second took us all the way to Rurrenabaque, about five hours away.

The road between Caranavi and Rurrenabaque was in surprisingly rough shape, and this part of the trip was an adventure in itself.

Large sections were unpaved, and in those unpaved sections it was not uncommon to see cars or trucks stuck in mud. Luckily, we did not share their fate since those cars and trucks stood as markers for our driver of areas of the road to avoid. To my delight, the sides of the road were also dotted with people selling mangoes, as we were passing through mango country during mango season.

Some trucks stuck in the mud on a road near Rurrenabaque.

After everyone had their fill of mangos, the other people in the colectivo started to share what they had brought. A bottle of whiskey made a few trips around the car, and even the driver had a few swigs. Between sips of whisky, people also shared cigars and handfuls of coca leaves.

With so much going on, time flew by. Before I knew it, we had arrived in Rurrenabaque, the city at the crossroads of the Andes and the Amazon.

The town of Rurrenabaque, the Río Beni, and the vast Amazon basin beyond.

Las Pampas

From Rurrenabaque, the first tour we took was a three day trip to Las Pampas, a protected wetland and a popular ecotourism destination due to its abundance of large animals.

To get there, it was a several hour car ride from Rurrenabaque down a dirt road. Once we arrived, we loaded our things into a motor canoe and took off into the wetlands.

To say there was an abundance of large animals was probably an understatement. As we traveled through the wetlands, there were animals everywhere. The banks were lined with alligators and caimans, some well over ten feet long. Resting a healthy distance from them, we saw capybaras, different kinds of wading birds, and the occasional snake. In the trees, we saw three different kinds of monkeys and an even greater variety of birds.

Although opaque, we could tell the water was full of life as well. On occasion, we would see the snout of an alligator or caiman pop up on the surface near our boat. We also saw birds dive into the water and emerge with a fish or snake in their mouth. At one point, we stopped our boat to watch two pink river dolphins periodically break the surface to take a breath while they hunted for fish.

All of this took place over the course of just a few hours. By the time we made it to our tour company’s screened-in cabanas, the stifling afternoon heat and humidity had set in, so we stopped for a few hours to take a siesta.

We emerged again in the evening to watch wildlife a bit longer, until returning to camp when darkness fell. At night, Las Pampas was a different world entirely.

Many different kinds of frogs and insects made a racket so loud it was, at times, hard to hear. There were bats everywhere, but I had no idea how many since I could only see them when they flew right past me in pursuit of insects. In the darkness, we could also see luminescent flying insects locally called luciérnagas. And most surprisingly of all, compared to the day there were relatively few mosquitos.

Once I could not take in the sights, sounds, and smells any longer, I went to my cabana to go to sleep.

Our guide saying hello to Pepe, a 13-foot caiman who had visited the cabanas almost every day for the past 20 years.

The next day, we were up with the sun for what our guide, Juan Carlos, called the Anaconda hunt.

Although it was not really a hunt, since we were only going out to try to find one, not kill one.

The fascination with anacondas, though, is well-warranted. They are both the world’s heaviest snake and one of its longest. In the Amazon, they can grow up to 20 feet long and weigh over 200 pounds, though in the more remote reaches of the Amazon they might grow even larger.

But luckily for us, despite their large size, anacondas are not known to eat people. That honor instead goes to the reticulated python of Southeast Asia, the only snake that has been documented eating adult humans (although this has only occurred a handful of times throughout recorded history).

The anacondas of the Amazon instead hunt the birds, mammals, and reptiles that hang out near the water’s edge. Here they like to remain submerged until they can strike out and constrict any animal that wanders too close. So to find them, we journeyed to an especially swampy part of Las Pampas our guides called the pantanal.

Following Juan Carlos (right) through the pantanal.

Unlike the rest of the wetlands, which followed a branching stream through a dense forest, the pantanal was a wide lake hundreds of feet in diameter that, at its deepest point, only went up to the knee. Due to the absence of moving water, the pantanal was completely covered with floating vegetation, offering infinite hiding spots for hungry anacondas.

Juan Carlos warned us, however, that anacondas were not the only hunters here. Alligators and caimans also hung out in the pantanal to grab animals that stepped too close.

Like the anacondas, the alligators and caimans here did not hunt people. Their typical prey was considerably smaller than a human, so they typically were not too inclined to tangle with someone as large as a person. But they could be territorial and aggressive when surprised, so we were each given a stick to feel the ground in front of us while we walked to ensure we would not be stepping on a sleeping reptile.

“How polite,” I thought.

Among the floating plants in the pantanal, there was one in particular that caught my eye, la Reina Victoria, or Queen Victoria water lily. These giants have some of the largest leaves out of any plant in the whole world, and some have even been large and strong enough to support the weight of a person!

One leaf from la Reina Victoria.

But my fascination with the water lilies was cut short when I heard Gabe, who was walking right behind me, yell “joder!” Or, fuck! Followed by a loud splash.

I turned around just in time to see an alligator’s snout sinking back into the swamp. Apparently, Gabe had surprised an alligator and it lunged up at his stick.

Not wanting to tangle with it, he and everyone behind him ran back to the safety of dry land. I however, had no such option, since the splash was directly between me and shore. There was an alligator within feet of me, but since it had submerged itself I had no idea where.

“They do not hunt people, they do not hunt people,” I kept telling myself, but some phrases are much easier said than believed.

Just the thought of the alligator gave me an adrenaline rush that would make any whitewater rafter jealous. But I was able to pull myself together enough to yell to Juan Carlos, who was perhaps 15 feet ahead of me:

“Que debo hacer?” What should I do?

He instructed me to move slowly and proceed as I had been, feeling the ground ahead of me with the stick.

One step.

Nothing happened.

Then another.

Soon I felt I had put enough distance between me and the hidden alligator and was able to fall into a comfortable rhythm, although this time I made sure to stay right at the heels of Juan Carlos and step exactly where he stepped. We talked as we walked to ease my lingering fears, and he told me that once we were out of the pantanal, he had a story to tell.

We walked and searched for a while longer, but eventually the heat and sun became unbearable. We called it a day for the hunt, and even though no one had found an anaconda, I felt I had enough thrill for one morning.

As we walked back to the cabanas, I asked Juan Carlos about that story. He responded by pulling up his left pant leg, revealing several long scars and a tooth buried beneath his skin. Exploring this same pantanal with his friends as a kid, he had his own tangle with an alligator.

Walking through head-high grass on the way back from the anaconda hunt.

After that, we spent the next day and a half watching more wildlife (from a safe distance). Although every minute was incredible, nothing too out of the ordinary happened, and we were returned to Rurrenabaque bitten only by mosquitos.

Trekking Through the Jungle

After the tour of Las Pampas, the last adventure on our agenda was a trek into the jungle itself. From Rurrenabaque, we would travel up the Río Beni into Parque Nacional Madidi, where we would spend three days backpacking with our guide.

For many reasons, Parque Nacional Madidi is considered one of the world’s greatest national parks. The park itself protects a variety of habitats, ranging from the high Andes down into the Amazon. Along with several other adjacent national parks and forest reserves that span all the way into southern Peru, Madidi is part of one of the largest protected areas in the world.

Furthermore, it might also be the world’s most biodiverse. Over 1,000 different kinds of birds are found here, which is more species that are found in the entire United States (1). Put differently, this national park covers considerably less than 1% of the Earth’s surface, yet is home to over 10% of its bird species. Talk about a valuable ecosystem!

Excited to see the jungle on foot, we loaded into a motor canoe for the several hour journey upriver deep into the national park.

Heading up the Río Beni in a motor canoe.

I was told that ecotourism in Rurrenabaque was first put on the map in 1981, when an Israeli backpacker on an Amazon expedition gone-wrong survived three weeks in the jungle with no outside food or support. When he was eventually rescued on the cusp of death, his story made international news. He went on to write a book that was eventually adapted into a movie, and his story led thousands of other travelers to come to Rurrenabaque to relive his adventure (2).

Due to this history, our jungle trek had threads of wilderness survival woven into it. We would be building our own shelter, foraging for food, and doing all of our cooking over a wood fire.

The shelter we made from bamboo and palm fronds.

I found this aspect of the trip fascinating. While I had been on countless backpacking trips, I had never once trekked through the forest looking for food with an expert local guide.

And our guide, Micky, was certainly an expert. He showed us which vines we could cut open to find potable water, which fruits were full of maggots that we could use to fish, and how to cut open a young palm tree to eat its sweet, tender interior. He even treated my allergies with a mixture of alcohol and bark from a specific tree.

Beyond that, he was also full of stories about life and traditions in the area. Every morning, he walked us through the process of burying coca leaves and a burnt cigar as an offering to the Pachamama, or Mother Earth in Quechua. Pachamama is an important figure in many local indigenous cultures, and here was no exception. By showing our respect through offerings, she would reward us with safe passage through the jungle.

While burying our offerings, we also had to watch out for the inch-long ants that dotted the forest floor. La hormiga bala, or bullet ant, is said to get its name because it packs a sting so painful it is comparable to being shot with a bullet. Mickey told us that multiple times he had to end trips early after a customer was stung.

These ants are used by many local communities as well. Mickey said that just outside of Rurrenabaque, there is a tree with a nest of bullet ants right at its base. Due to the limited police presence in rural Bolivia, when someone steals, scams, or otherwise hurts the community, everyone works together to catch the culprit. When caught, they are then tied to the trunk of the tree, which one volunteer proceeds to wack until the bullet ants emerge angry and ready to sting.

And bullet ants were just one of many bothersome insects. Mosquitoes and biting flies swarmed day and night. The first night, I went to sleep without realizing there was a gap between my mosquito net and the ground. I slept shirtless and on my stomach without waking up once. The following morning, however, I realized that my back was polka dotted red from the bugs that had feasted on my undefended back.

They say that in the Amazon you are part of the food web.

The jungle was also really hot from around 10 am to sunset. Although the dense forest canopy shaded us from the sun, it also sealed in the humidity. Just 15 minutes of walking would have me drenched with sweat. Having worked an outdoor job during the second-hottest summer in Texas history, I am no stranger to the heat. But what I had not considered was that during the preceding months I spent in the Andes, I had lost my acclimatization for the heat. So while the heat here was comparable to what I had experienced previously, my body was not prepared, making the weather here especially difficult.

Cooking over a fire.

On our last night in the jungle, we prepared ourselves an especially nice meal. We had crossed through an abandoned plantain farm earlier that day and found a number of ripe ones. I also caught a catfish using some grubs we had pulled out of a fruit, and Mickey showed us how to cook it with vegetables inside of a bamboo cane. So as we laughed, told stories, and mourned the end of our adventure from La Paz to the Amazon, Gabe and I also enjoyed what was probably the hardest-earned meal of our lives.

The meal of rice, plantains, vegetables, and catfish.

We were both very exhausted and ready for some rest, but I was still sad to go. I realized that I am not done with the Amazon. It is a fascinating world—full of life, yet often unforgiving. Sitting on the forest floor, its importance to the health of the entire world is readily apparent. Its incredible diversity of life is unlike anything I have seen in any of my previous travels.

I am currently looking for a way to return and see more of this incredible place, since as its many indigenous peoples already know, you can spend your whole life there and still see something new every day.

A nest with baby hummingbirds inside.

Christmas Eve in a Bolivian Hospital: An Epilogue

In all my years of hiking, paddling, backpacking, and otherwise trekking through remote areas, nothing has kicked my ass as thoroughly as that trip from La Paz to the Amazon. Still, eventually, the soreness faded, I forgot about the miserable heat, and the bug bites healed. I felt well-rested and rejuvenated for about a week, but then I started to feel a little funny.

My muscles started to ache, I had a pounding headache, and most concerning, taking a step would give me a weird feeling that felt like my organs jostling around in my torso. Then, on Christmas Eve, I developed a fever.

At that point, Gabe and I were in Sucre, a major city in Bolivia. We decided it was time for me to see a doctor and went to a nearby medical clinic. There, I told the nurse about my symptoms, which prophylactic antimalarials I took, and my recent travel into the Amazon.

Like me, he was concerned about the possibility I had contracted a mosquito-borne illness, but even more concerningly he said there was nothing they could do. Specifically, due to the Christmas holiday, all medical labs in the country would be closed until December 27th. So it would be impossible for me to get a test result or specialized medical treatment in Bolivia until then.

Once I had taken in the news, they gave me a big shot of fever reducer and said to come back on the 27th if I still felt sick.

Christmas arrived, and I still felt sick.

Then December 26th, and my headache grew worse, not better.

I started making plans to return to the medical clinic and mentally preparing myself for the bad news they would give me. I went to sleep on the 26th expecting the worst, but miraculously, I woke up on the 27th feeling just fine.

The fever was gone, the headache was gone, and I could jump up and down as much as I wanted without feeling like my organs were bouncing around. So I changed my plans, and instead of visiting a medical clinic, visited Salar de Uyuni, one of Bolivia’s top tourist attractions, instead!

Isla Incahuasi in Salar de Uyuni.

References

- Identidad Madidi Announces 1000 Confirmed Bird Species For Bolivia’s Madidi National Park. WCS Newsroom (2016), (available at https://newsroom.wcs.org/News-Releases/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/9090/Identidad-Madidi-Announces-1000-Confirmed-Bird-Species-For-Bolivias-Madidi-National-Park.aspx).

- Simon Round, I was lost in the Amazon jungle. The Jewish Chronicle (2016), (available at https://www.thejc.com/news/all/i-was-lost-in-the-amazon-jungle-1.3956).

Páramo:

Páramo: